Why do you need a safety case?

Covering the basics for writing one of the most important documents for your project.

This is a two-part article that covers the why’s, how’s, and what’s of safety case creation. The first part covers the fundamentals and the classic composition of a safety case, while the second part delves into newer approaches within a safety case framework which alters the fabric of safety assessment and risk reasoning.

Part 1: What is a safety case?

A safety case is mostly a collection of relevant design and verification artifacts, reports, and processes applicable to your project or robot. Everything that anyone has worked on in relation to your project; documents, tests, schematics and plans are all part of that. Its a good idea to have a safety case, no matter what your product is. Safety cases can range from a simple folder containing documents to an intricately developed argument or strategy that effectively conveys a specific message.

Why would you need a safety case?

There are two major reasons to make a safety case: First, for you to know the safety limits and risks of your own product, and second, for others to know the safety limits and risks of your product.

Almost all engineering projects will have some interactions with humans, ranging from one-time interactions like employees during manufacturing and assembly, or the customers within general public using the project every day. This means engineering or safety teams have an obligation to consider risks associated with human interactions, whether or not those interactions are part of the intended product operation. A great way to do that is to create a safety case.

Before we dive into the work itself, it is crucial to understand the purpose of your safety case. What is your main objective for it? Who will be reviewing it, and why? We will go over these key questions and a few others to help safety case creators and reviewers with their important work.

What is the purpose, who is the audience?

Knowing your objective for the safety case early on ensures its effectiveness and completeness. You get there by answering questions like: “What does safety case do for my company or project? What is important to my company and my clients about this project?” Depending on your goals, you will include or omit specific information, determine a method of presentation, and alter the language in which it is written. Even if you create a safety case solely for compliance with a specific industry standard, the “why” (why this standard, why do we follow this process) should be a key component in your safety case.

Some examples of safety case purposes include:

Highlighting open risks to leadership and board members,

Demonstrating compliance to internal safety processes,

Proving that safety objectives have been met,

Providing a concise summary of safety efforts for a specific project for internal review.

Another aspect to consider is your audience. Are you sending this to a regulator or is it an internal log of activities? Is it for your non-technical CEO or for a safety consultancy company supporting your regulatory efforts? As with any writing assignment, considering your audience and your main message is crucial. If you expect a review and feedback from non-engineers, you should carefully consider how to emphasize key messages for them without altering the risk picture. If it is written for a regulator, extra attention should be paid to include company specific details, traceability, and descriptions to internal processes.

What should it look like?

The method of presentation depends heavily on the audience and the purpose, as I mentioned before. There are simple and complex ways to present your safety case, ranging from a list of documents presented in a table, to text based summary, to a detailed graphical representation of the safety claims and safety arguments.

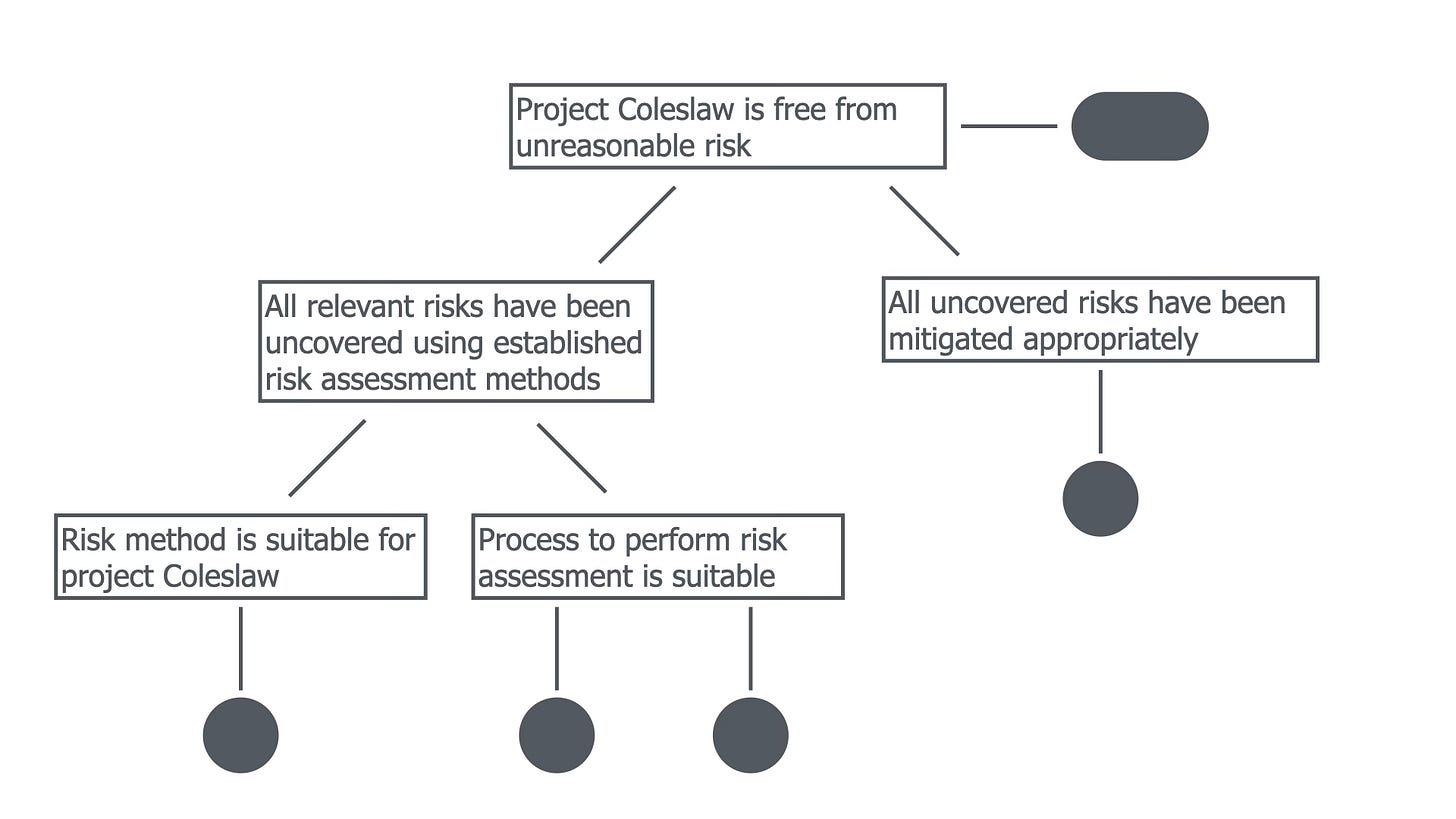

Although each method has its advantages, it is certainly beneficial to carefully consider a detailed visual safety argument. This approach focuses your efforts on achieving the goal (or safety claim) you have set out for the product and the safety case first and foremost. Leveraging the argument tree can highlight gaps in the design and safety claims relatively early in the product development and fix them before the product is finished. In addition, large parts of the safety case could be reused for future uses both on the product and on the process side.

What should it include?

Safety cases often have a main focus based on the project or product and the objective of the safety case itself, but they should still cover the following aspects:

Product and process,

Development and validation.

I’ll briefly talk about the benefits of both pairs, but rest assured that safety standards such as ISO26262 cover both parts of both pairs in depth too. Taking inspiration from relevant standards is a great idea to ensure a well fitting, well structured safety case.

Products and processes should go hand in hand, doing one is how you develop the other.

The claim that your product was developed and tested well is best supported by the fact that your team or company leverages good processes to support this development and testing. And if you offer a product that relies heavily on processes, a product component development and validation argument can reinforce the validity and completeness of the company processes.

Even if it appears that only one of the pair is part of a development or as a company output, the other likely still exists. A startup selling small figurines depicting sleeping animals has surely considered the manufacturing, dying and quality control processes surrounding the snoozing animals for sale. And a company developing a new methodology for cleaning your bathroom cabinets has likely been iterated over the course of several different homes.

Most classic safety cases from established industries that I have worked on and come across leverage both development and validation strongly. There would be detailed arguments and documents depicting where the requirements have come from and how that leads to a design. Verification and validation would be argued in terms of meeting requirements, completing certain integration checks, and testing the final design both in terms of requirements and in terms of performance in the real world. Depending on the safety risks associated with the product in question, the safety case should be more or less detailed.

Development and validation as a balanced pair in product development and safety cases has gone through an interesting shift in the last few years. I’ll spend some time diving into how this impacts risk and how we can offset some of that.

Other considerations

Before you start off writing safety cases for all your projects, it makes sense to consider a few more realistic aspects.

Reuse value: Perhaps your company considers this project a dead end, meaning that there is no expected rework or revision on this. You can consider looking at the specific parts of the safety case that are not going to be reused and, if appropriate for the project, the objectives, and the risks, consider making that part simpler, condensed, or pointing to existing work documents directly.

Signing off: If there is an objective to have one or more people sign off on a safety case, consider how that will be done practically. It could be done with a front page or summary and a digital signature, a formal review or meeting where attendance and confirmation are recorded, a different digital approval system, and even a good old fashioned signature on paper. While none of these approaches are specifically bad, I would not advise email-back approvals in particular, because they may allow an approver to be slightly detached from the actual material they approve. For that same reason, I have a preference for requesting a hand-drawn signature for certain projects. Asking people to physically write their name on the dotted line makes them pause more that you might think.

Distribution and publication: In some cases, the safety case will be distributed to external stakeholders such as suppliers, customers, or regulators. Or a company can choose to make the work available to the public for review as a marketing piece. It is important to be mindful of this so that you can ensure your language and content make sense to the audience. I would recommend discussing the distribution or publication with the right people in the company to ensure that everyone is aware of the work and its outcome.

Resource constraints: Building a good safety case takes time and resources, and it is likely that one or both of those are constrained or reduced over the duration of the work. This is unfortunately quite a common issue and is difficult to solve. It is possible to use your safety case objectives and audience together with any potential safety arguments already created to highlight the criticality of the work. If the original scope of work remains out of reach, you could carefully and with sound documented reasoning reprioritize certain parts of the safety case. A smaller, simpler safety case is better than no safety case at all. Always document the reasons for omitting and simplifying, and consider making a list of high priority next steps to make it easier for anyone will work on this next.

Next week I will cover the future of safety cases and how complex technology fundamentally shifts how we argue safety as a community. Subscribe if you don’t want to miss it.

Example Safety Cases

Here are three very small examples of hypothetical safety case approaches for illustration purposes.

Table

Project plan for Coleslaw project — Approved by J. Grill, April 2, 2022

Coleslaw system design document — Approved by J. Grill, April 30, 2022

Coleslaw system test document — Approved by J. Grill, June 20, 2022

Barbecue Company test processes

Coleslaw project review and release meeting minutes July 12, 2022

Summary

The Coleslaw project is a natural evolution to Barbecue Company’s Side Dish program, and has been developed using mature design processes. The requirements have been developed in conjunction with the customer and verified in our testing processes and pilot deployments. The testing methods leveraged for this project have been iterated on quarterly over the last 5 projects. All tests have passed and all known risks have been mitigated appropriately. The project and its key documents have been reviewed by the company leadership, internal safety experts and internal senior subject matter experts.

GSN or CAE

This is a very small example project with minimal risk, and the methodology and reasoning is highly simplified.

For more information on GSN, please visit the UK based Safety Critical Systems Club website here. For CAE, please visit this page.